Here is a photo of my mother aged fifty, the age I am now. It was taken on the edge of a flat place called Crowland. In 1989 we travelled across the fens from Norfolk to Nottinghamshire in Mum’s wagon. We went back to take care of Granny. Granny lived seven years longer than Mum did. Rich people live longer than poor people, that’s the way it goes.

Mum may not have been rich but she was free. Wilfully unshackled from the expectations of her class she gave what little she had away, this included her love. In 1998 she asked me to travel with her across the fens again. I drove the dealer’s cart, Mum drove the wagon. It took us two weeks. Afterwards I wondered if Mum felt able to return because her mother was dead. No one left to disapprove.

When she got there, Mum set up camp by the roadside. She cooked under an umbrella by a tumbled down barn belonging to her brother. She became territorial. It was as though the fields and old rocks were her family. She patrolled the park, village and graveyard with her dogs, scowling at anyone who dared to disturb the earth with frivolous rose bushes or defile farm gateways with bags of urban rubbish. For her these places held roots buried deep, bones of loved ones sunk down beyond the cold limestone,

‘All of my relatives are buried here,’ she once said to me as we closed the churchyard gate. Those graves were her friends.

We buried Mum next a hedge full of chattering sparrows. They chitter and chatter and sometimes poo on her headstone. Even though she wanted to be buried close to her beloved grandfather, I feel sure she likes being close to the birds. For more than sixty years wild hedgerows were her happy place. It feels apt that this is her final resting place. She never did hold much stead for decorum.

But back to the past, those fens, that watery, flat, dry place…

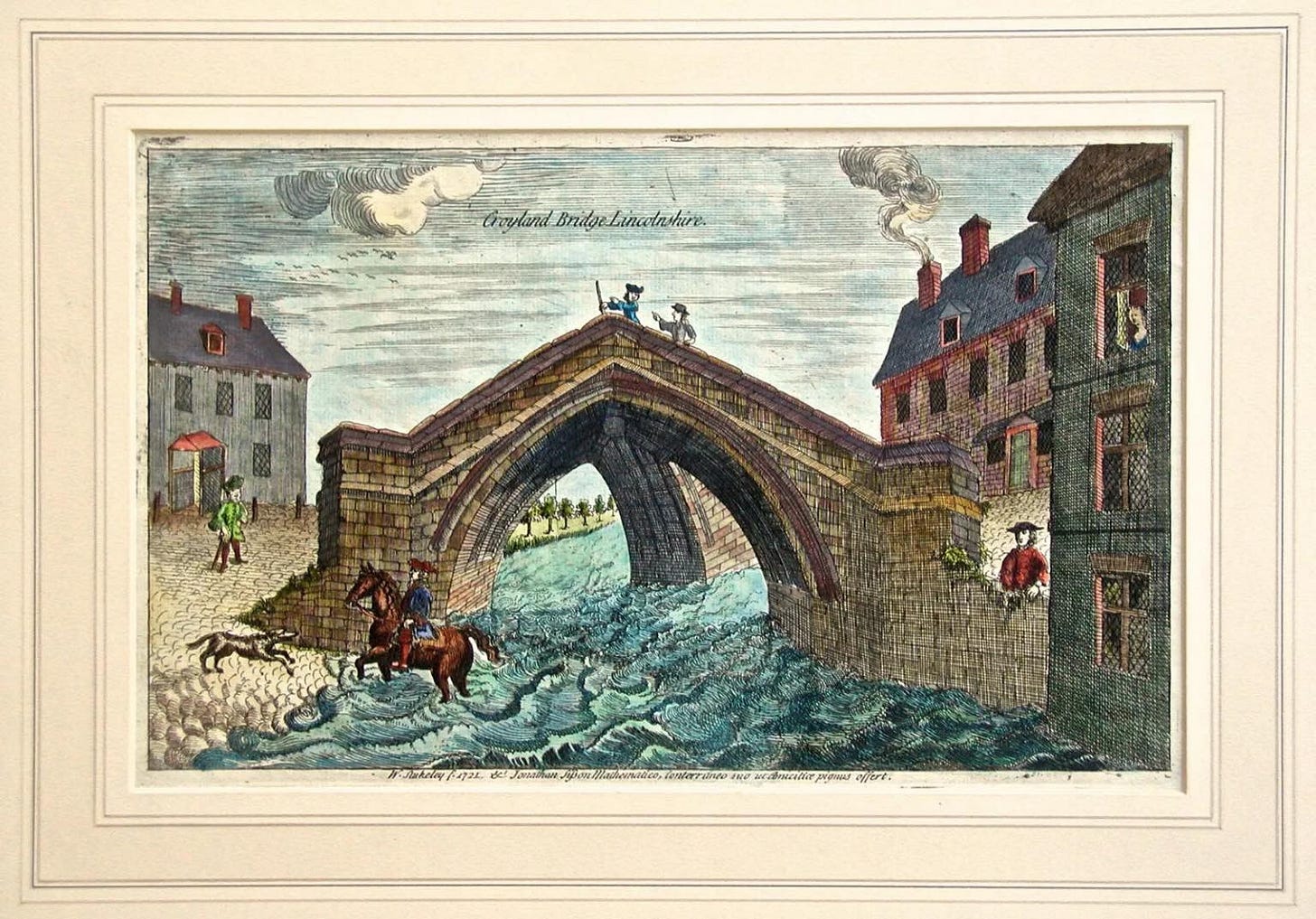

We got lost around Crowland. I remember asking a young woman the way to Market Deeping. She pointed ahead, instructing us to ‘go up that hill’. Mum and I looked and looked but saw not a hill in sight. Only a barely perceptible incline by the river Nene. When we got to Crowland we found a seemingly pointless ancient bridge. What was this place? Why this incongruous looking medieval bridge?

I googled the bridge to discover its past…

“This unusual bridge (the only one of its type in England) was built at the point of the confluence of three rivers- the Nene, Welland and Catt, because of this it had three arms which met in the middle. Now the rivers have been diverted and the 14th century bridge no longer serves a practical purpose. Attached to the parapet of one of the arms is a carved figure which has been depicted in this print. The statute is approximately life size and it is thought that it once stood in the west façade of Crowland’s Abbey church. The features of the statue have been worn away over time so it is not possible to definitely identify the character however many believe that it is the Saxon King Ethelbald. Originally the bridge was surmounted by a canopied cross where pilgrims may have stopped on their journey to the shrine of St Guthlac.”

[South Holland Heritage]

I remember Crowland Abbey. I remember seeing a sign for South Holland amongst the fields and fields of flowers, veg and orchards. The breadbasket of Britain.

I got lost around Wisbech back in 1989. I was fourteen. Mum had asked me to cycle into town to her buy a frying pan. An academic who wrote papers for the Gypsy Lore society was travelling with us. He spoke very slowly and when he walked we could hear pills rattling in a plastic bottle he kept in his trouser pocket. Mum treated him like a child because he spoke slowly and sometimes slurred his words. He annoyed me. When we got to the shop he insisted on choosing the frying pan, but Mum had asked me to.

I was so cross I cycled off, far ahead of the wagon and got lost. I must have cycled forty miles that day. In the end I turned back for Wisbech. I found a phone box and rang my brother,

‘Meet me on Wisbech common’ he said, ‘I’ll come and get you.’

I passed a pub with a sign in the window, ‘No Gypsies’ it said. I asked someone I met walking along the road if they’d seen a green wagon pulled by a small brown pony. They said they had, just round the corner; but I couldn’t find it. I discovered later that I’d been within a quarter of a mile of finding our wagon. I gave up and turned back.

Meanwhile Mum had rung the police. This was the day before her fiftieth birthday. She’d wrung her hands and feared the worst. No one knew where I was.

I lay down on a bank by Wisbech common and waited in the gathering dusk for my brother. A police car pulled up. A man got out and squatted down beside me,

‘Are you lost?’

‘No. I’m waiting for my brother.’ I answered, avoiding his gaze.

‘I think you’d better come with me, down to the station.’ the policeman said, ‘your mum is worried about you.’

‘I can’t.’ I replied, staring straight at him, ‘if my brother finds I’m not here, he’ll get a terrible fright!’

‘You come along with me.’ the policeman said getting up and opening his car door, ‘is this your bike?’

I was driven back to the wagon later that night. It was well after dark. There was no shouting. I felt Mum give me a look, followed by a loaded silence. Academic pill man stood by the fire, his arms limp. I went straight to bed, heart pounding, fearful of tomorrow’s wrath. I heard murmuring outside. My brother lay down in the long grass. He sounded subdued. Mum put the kettle on,

‘What did you think when she wasn’t there?’ I heard her say,

‘My heart was in my mouth.’

Silence.

The crackling of the fire.

The guilt.

August the twelfth 1989. How could I get lost the day before Mum’s birthday? She must have been worried sick. It was the academic’s fault. Stupid man. If he hadn’t bought the frying pan. I would never have got lost. I closed my eyes and sunk into the oblivion of my aching legs.

Fenland is a strange and mysterious place. Not many folk want to live there, most people find it boring. I find it captivating, a place of wonder and etherial nothingness. A poetic place. Empty of people yet full of produce. Every scrap of land fertile, fecund. Flat and wide. Poplar lined fields interspersed with long straight drains brimming with dark silty water. Vast swathes of borrowed land, much of it below sea level. A brooding place haunted by floods.

Fenland’s history is obscured by its drainage. Pumps, ghostly ruined windmills, concrete bridges and memories of water. People used to get about by boat, sometimes on stilts I’ve been told. In the old days it was hard to find an unrelated mate. Incest was not uncommon, but this was the case in many other disparate parts of England including remotest west Cornwall, the far flung region I now call home.

Some say history is circular. The past feels smokey yet real, part of now, yet not. Where does the essence of absent loved ones go? Do they remain buried deep in the dark earth? Or do they hover somewhere; over the fens maybe, re-living the old days. Do they come to meet old friends and beloved animals in the middle of the air? Do they roam amongst pastures green and fair, by waters still and calm? Is she smiling? Yes. When I dream of her.

The more I learn of your mother, the more I appreciate how brave and free spirited she is.